There’s much to admire about a group of volunteers who get together on a regular basis to ensure a restoration project is one day complete. Justin Felix steps inside the B-24 Liberator Restoration hangar in Werribee, Victoria to discover more.

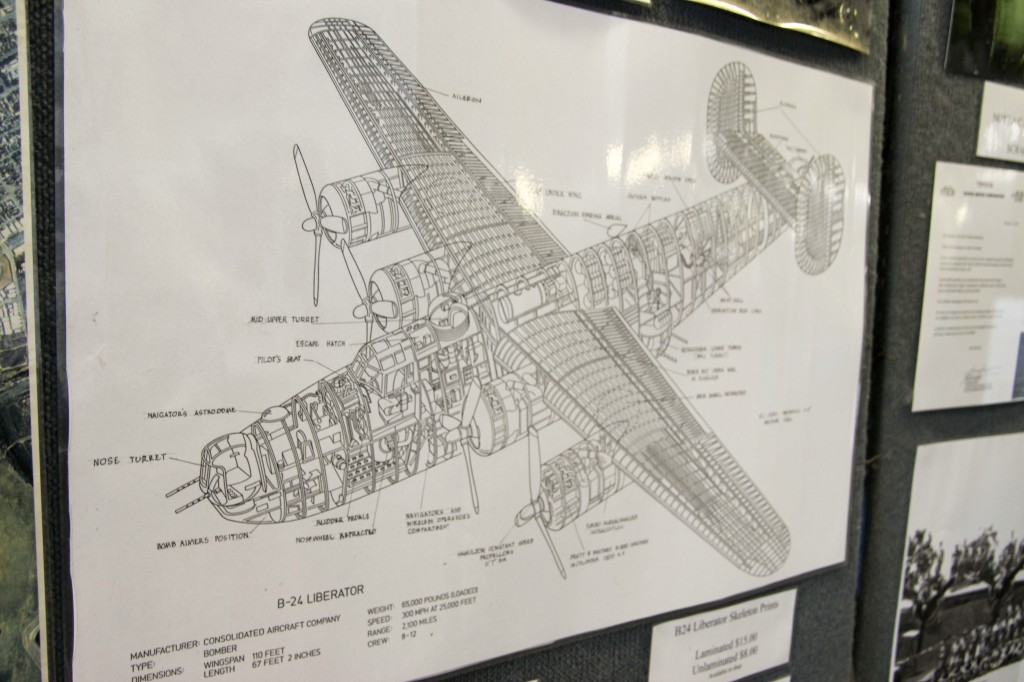

The B-24 was a long range heavy bomber used in World War II by several Allied air forces and navies. The Americans sensed the impending war and chose to upgrade their Air Force with the B-17 and B-24. The B-24 holds the distinction as the most-produced American military aircraft and at one stage – thanks to Henry Ford – they were producing one every 59 minutes. That’s a staggering production feat today, let alone in the 1940s.

Back in 1988 a group of ex air and ground crew got together with the aim of creating a memorial for the2 people that flew B-24 Liberators during the war. They met every month at the Brighton Yacht Club and chatted over a few beers before they came across a fuselage in Moe, some 130km east of Melbourne.

The Liberator stands proudly in the centre of the shed while various work stations are situated around the place.

A man had bought the fuselage at an RAAF auction. He threw away the wings, tail plane and engine before he had the fuselage moved up to his farm in Moe. In that particular point in time there was very little building material available to build houses so he lived in it for 7.5 years. In today’s day and age it could be considered the Rolls Royce of caravans.

The Brighton Yacht Club crew negotiated with George to eventually purchase the fuselage to form the start of the restoration. It was about 1994-95 at this stage. Unfortunately the fuselage had been engulfed by bush so the guys had to rescue it from the scrub before bringing it to Werribee in 1995. They had a terrific vision for the completed project and one step into one of the World War II hangars on the old Werribee airfield just outside Melbourne, reveals just how far that vision has come.

A team of 45 skilled volunteers work on the restoration three days a week which ensures progression is never stalled. The majority are long-term volunteers but new volunteers come through sporadically. Most are retired and aged 65-90 but a sprinkling of younger guys get involved as well.

This aircraft is the only one of its kind in the southern hemisphere and will be the only one in the world fitted out internally.

It’s a noisy place as I discovered on the day of my visit. A constant hum of machinery resonates in the background but it’s nice to hear work-in-motion in a place like this. Welders work in one corner while sheet metal workers forge creations in the other. There’s a bench section where groups of men converge and brainstorm on smaller projects while three or four guys are busy working away on the bomb bay inside the fuselage. An air raid siren signals tea break and a well-earned rest is used to refresh and rejuvenate.

The restoration project has created a platform for both the young and old to collaborate ideas and put skills to good use.

It’s a restoration of epic proportion but it’s one that has come a long way. Future Development Coordinator, David Miller, provides some insight as to how the project has advanced so admirably.

“We sat down six years ago to create a 10 year plan that would provide us with a clear view of where we wanted to be and a five year plan for where we envisioned the aircraft to be. It gave the volunteers and the supervisors (a term David uses loosely) some much needed direction. It means we always have something for the guys to do. There’s nothing worse than a volunteer organisation that has nothing for the volunteers to do,” he explains.

“The majority have some recognised skill and when somebody expresses their interest in becoming a volunteer we ask them what they want to do. We recently had an electrician come in who always wanted to be a sheet metal worker so he started out working with the sheet metal guy and within three months he was making bits and pieces for the aeroplane. We also took advantage of the fact that he was an electrician as he could sign off on any electrical work that we required, whether on the plane or in the hangar.

“We try to keep the volunteers interested and we also encourage people to pass on their skills rather than hold on to them.”

An incredible amount of sheet metal work and 400,000 rivets later and the restoration and preservation of the fuselage is complete. The guys are currently fitting it out with hydraulics and David explains that there is a fair bit to do on the wings and some tidying up of the engine. Their biggest task is putting the electrical system in though.

“We’re good with engines and sheet metal but not very strong on the electrical side so we have to learn. We’ve got two experienced electricians here but it will take a team of 10 or 12 to get the job done.”

There are plans to refurbish the current hangar to hold three aircraft with the hope of building a hangar solely for the B-24 Liberator. Having its own hangar will mean the team can start the engines and turn on the flying systems. In essence, it will be alive but won’t ever fly. The plans have been submitted to heritage and state government and from all accounts they like them, they just need to put pen to paper.

It would be easy to mistake the hangar’s crew for being part of the Australian Men’s Shed Association but David explains that the B-24 Liberator team chose to go it on their own.

“We did discuss the possibility of joining the Australian Men’s Shed Association but we’re quite content with being self-sufficient. Financially we’re pretty well self-subsidised which we’re happy about because we can spend the money however we see fit. We have about 400 members worldwide and memberships cost $33 per annum. We also have a gift shop in the hangar and rent the space out for functions. Engine runs always attract a good number of people and daily tours provide a steady income stream. We’re very lucky to have the treasurer that we do. He strongly believes that ‘the easiest thing in the world is to spend other people’s money’, so we don’t’.”

For visitors to the hangar, there’s more to see than just the Liberator. The entrance is flanked by memorabilia of a bygone era. There are old photos, equipment and ammunition on display, as well as Liberator parts that have been pulled from wreckages around the globe. Historical photos depict the poor shape of the fuselage as it arrived at the hangar and with the restored plane standing in front of you; it’s hard to fathom the amount of work that has gone in. David explains that reclaimable parts were stripped and rejuvenated while parts that couldn’t be salvaged were used for obtaining patterns.

When you see the quality of the work on display, it’s hard to imagine that the plane was nothing more than a beat up shell when it arrived.

“We started up just as machinery was transitioning to CNC and robotics. We were lucky as the machinery donated to us was of a time that most of the volunteers were accustomed to. I don’t know if the guys would have been able to adopt to the new technology… they’re the type of men who bend steel with their hands.”

The volunteers will never be redundant at this place. There are plans to re-build a wooden Airspeed Oxford training aircraft next. The skills in restoring the Oxford are equivalent to the skills required to rebuild the B-24 just with different materials.

The older guys who weren’t too keen to climb up on the B-24 have now started on some bench work for the wooden plane. Even after the Liberator’s restoration is complete, regular maintenance will be required and just like the continual work; friendships continue long after a working day is over.

“We’ve found that the men here are really involved in what they’re doing and on the days that they aren’t here; they’re calling their mates to tell them what they’ve been up to. It’s a great way for the guys to forget about the bad backs, elbows and other aches and pains that come along with age. Some of the younger guys have really come out of their shells by being here too.

“We encourage aircraft engineering students to come here and gain some hands on experience. It’s important that we pass on our skills and empower people. If one in 10 of the young people come back to work here in the future then we see it as a success,” David says.

Success is probably the best way to define the project. The ultimate goal is the restoration and preservation of the Liberator but for the men that work here, it has defined friendships, renewed confidence and for the younger guys, offered unrivalled experience and mentoring. To see them all work in unison to ensure the dream became reality was certainly a liberating experience.

Contact:

B-24 Liberator Australia

www.b24australia.org.au