There are more than just cows to be found on Keith Cameron’s farm in NSW, as Ian Kenins discovers.

Keith Cameron is not your average farmer. On his property in Tabulam, a small rural settlement two hours west of Byron Bay in NSW, he has about 70 head of cattle spread over 440 acres, with a few paddocks set aside for corn, soya beans or oats, depending on the season. Otherwise there’s a lot more art than there is agriculture.

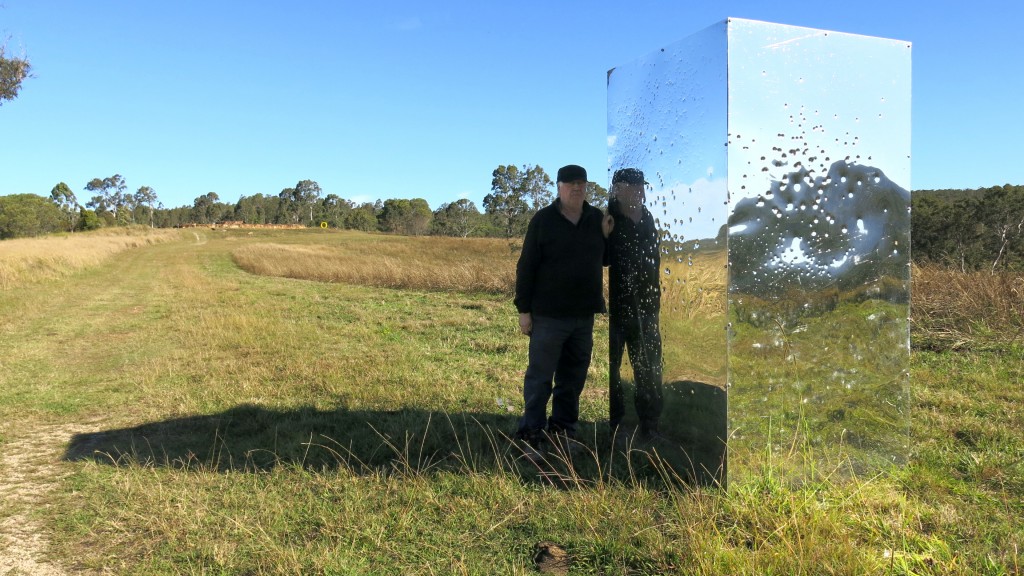

Keith is also a scrap steel sculptor and his works can be seen spread out over an open air gallery he created on his property by moving 500 tonne of huge stones and arranging them into Celtic circles. He and his partner Marion also provide accommodation for artists who might want to stay a little longer for further inspiration.

The works on display are mostly abstract: a large steel wheel sits atop a tall slender column; a rusted truck chassis forms the base for two weathered fence posts topped with steel domes and surrounded by other pieces of bent and straightened steel rods; steel has been bent and shaped to form a pentagon; more ‘practical’ are seats up to five metres high in varying colours; and what looks like a homage to the industrial revolution has dozens of steel wheels and cogs welded to contoured and straightened steel panels and rods. It looks functional yet frightening.

So how did this come about? Well, the seeds of Keith’s artistic interest are genetic. Not from his parents, who ran a sheep and cattle farm in Coleraine in Victoria’s western district region, but from his grandparents and great aunts and uncles.

“They were quite talented,” Keith continues, “doing traditional still life works, they learned when there were tutors travelling the countryside in the 1920s.”

Keith studied art and painting when he attended primary and secondary school during the 1950s and ’60s, and occasionally he’d pick up a paintbrush as a young farmer. “When I was about 25 I started to put bits of steel together, purely by instinct, as I hadn’t been to a gallery. It just seemed the thing to do.”

In 1985 he and his then wife Anne (who sadly passed away in 2010) moved to NSW on a 1200-acre property, but Keith still found time for drawing lessons… until the rain disappeared.

“In the 1990s there was a drought on and cattle prices were low so we were forced to find other income.”

Keith sold 800 acres but expanded his steel fabrication work for local farmers, making round bowl feeders, hay racks, troughs and panels and gates, and doing repair jobs.

Surrounded by all that steel and having all the right equipment and loads of space – his shed is 30m long by 24m wide and is 5m high – Keith took to sculpting again. “It’s still metal fabrication,” he explains, “Just a different outcome.”

So different that Keith is sure the locals reckon, “I should have a decent job and be doing something sensible.” But he’s used to that, even understanding of it. “I grew up in a very conservative area of Victoria, and live in one here, and farmers are fairly conservative and art’s not something that’s on their radar.”

However, some locals are happy to supply Keith with their scrap metal, for which he’s very appreciative. “A lot of people with no interest in sculpture or art at all will bring me some really good pieces. I might not use them immediately but I certainly will at some stage. The locals seem to know what’s rubbish and what’s good for me.”

While happy to accept their offerings, Keith doesn’t suffer from a shortage of material. The decade-long drought saw lots of farmers leave the land and Keith snapped up their old machinery and waste metal from clearing sales and now has 30-40 tonne of collected scrap. “I’m lucky,” he says, “Because it’s a big workshop and I’ve got gantries and cranes and a front-end loader and the heavy stuff can be handled with a tractor.”

With few restrictions it’s all a matter of imagination. “When you’re making a sculpture, you’re not too sure what’s going to happen. You put pieces together and it makes itself in a way. You’re visually looking at a lot of form and somewhere in the back of your brain it’s assembling things without your knowledge. If it’s a large work, and some of the works might be five metres high, you start with a base, or something that it builds from, and just start building with no idea what’s going to come out. Sometimes you might have a good idea and other times you have no idea at all.”

One piece, the industrial sculpture of wheels and cogs, took Keith over five years to complete: others have taken him 10 minutes. “The welding doesn’t take that long. If you’re in the groove you might get four or five pieces done in a day. If I’m not happy with a piece, it’ll sit there for a long time until I realise what I need, and sometimes that happens in a quite abstract way: walking outside I’ll trip over something and suddenly realise that’s the piece that’s missing for the sculpture I’ve been trying to finish for three years. You’ll then take it in the shed and discover that it fits neatly where it’s supposed to.”

Most of the works displayed in Keith’s sculpture park are made from naturally weathered materials treated with a rust inhibitor, which is like a clear lacquer. “The weathered look is really good and Penetrol gives it a bit of a shiny appearance but it remains totally rusty. With a lot of the raw pieces I incorporate stainless steel and the combination works really well. I’ll get materials like a plough made with great skill by a blacksmith 150 years ago and when you disassemble it you can give it a new life by putting it into a different form.”

Other pieces have been painted in bright colours and these are the ones that attract children, and Keith is happy to allow them to interact with the art however they like. His giant chairs are particularly popular. “People are fascinated with them because, I think, when you’re young, chairs are really big and there’s a strange connection with people and chairs and they all want to get up and sit in them.”

Over the years Keith’s work has won competitions and attracted the attention of buyers and galleries, and he’s been commissioned to design pieces for public spaces such as the Trial Bay Gaol on the central NSW coast. “The gaol was built for convicts in 1886 and it was used during the First World War when they put German immigrants in there. I had to make an interpretation sculpture of the furniture that would have been there at the time of the convicts and the German internees. It was all pretty plain furniture but I had to do it in steel, so it was all powder-coated and silicone bronze welded because of the salt air near the sea.”

These days Keith spends more time sculpting than he does farming, and when travelling, an art gallery is the first place he and Marion visit. “That’s the only way I get to see the real stuff.” He’s also got an extensive library of art books. “The books have been very important to my education,” and there’s the visitors to his sculpture park to look after. But the shed is where he spends most time. “I don’t do a lot of advertising like most artists because if you’re promoting yourself, you’re not making your art.”